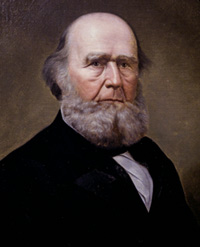

James Dinsmore

(1790 – 1872)

Born on August 24, 1790, James Dinsmore’s life is best characterized by his pursuit of wealth, status, the domestic comforts of a family, and a rational understanding of life and death. James was born in Windham, New Hampshire, the son of John and Susannah Bell Dinsmore. His Scotch-Irish father was a moderately successful farmer and innkeeper and was a part of the first generation to alter the spelling of his patronymic name from Dinsmoor to Dinsmore. Susannah Bell Dinsmore came from a prominent New Hampshire family that supplied the state with a Governor and a United States senator. Five daughters and three sons were born to John and Susannah, but the family was plagued with illnesses that took from James three of his sisters, his mother, and his father by the time he was twenty-four.

Born on August 24, 1790, James Dinsmore’s life is best characterized by his pursuit of wealth, status, the domestic comforts of a family, and a rational understanding of life and death. James was born in Windham, New Hampshire, the son of John and Susannah Bell Dinsmore. His Scotch-Irish father was a moderately successful farmer and innkeeper and was a part of the first generation to alter the spelling of his patronymic name from Dinsmoor to Dinsmore. Susannah Bell Dinsmore came from a prominent New Hampshire family that supplied the state with a Governor and a United States senator. Five daughters and three sons were born to John and Susannah, but the family was plagued with illnesses that took from James three of his sisters, his mother, and his father by the time he was twenty-four.

Like many Americans, yesterday and today, James wanted the kind of life that could only be had with a sizable amount of money. He had one personal defect, though, which his brother, John, described in a letter that compared their younger brother, Silas, to James:

He is your brother in every respect for in the first place he is always inventing sum (sic) new plan for me and in the next place he will lay in bed until he is called to breakfast and in the third place he will not work if he can avoid it and I think if I mistake not these are simtims (sic) of the same complaint that you used to be troubled with [and] father used to call laziness.1

After graduating from Dartmouth College in 1813, James taught school in New Hampshire and upstate New York. Realizing that teaching was not going to help him attain his goals, he moved to Natchez, Mississippi, near where his Uncle Silas Dinsmoor had once lived. Although he was raised in a part of the country where slavery was uncommon, he came to see that wealth and status in the American South derived from slaves and land. James began enslaving African Americans within a few years of his arrival in Natchez, but rather than make use of them himself, he hired them out to John Minor and received a portion of the crop their labor contributed to—something akin to a return on an investment. At the same time, he also purchased about eight enslaved people from his uncle to help the latter pay a debt he owed. Most of these slaves Dinsmore hired out to the U.S. government to build Fort Morgan near Mobile, Alabama. In Natchez, he allowed another enslaved man, Perry, to hire his own labor and find his own room and board, paying James a monthly sum. This practice was looked down on by many slaveonwers but the fact that men like Perry were able to provide for themselves independently, is a sign that the practice benefited both whites and blacks.

In 1828, James and John Minor, purchased land in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, from James Bowie that was to become a sugar cane plantation. Dinsmore was to manage the forty to eighty enslaved African Americans whose labor was to determine how wealthy he and his partner would become. Following the practice of some of his neighbors, James compensated the slaves for working in the sugar mill – the most detested but most important job – and working on Sundays and Christmas. The cash allowed them to buy some items they did not normally have access to, like calico, tobacco, and whiskey; the arrangement allowed a more industrious man named Allec to purchase his freedom, though it was not a legal emancipation. Dinsmore tired of Louisiana plantation life in the mid-1830s, calling the area a “moral waste” and resolved to move away, even if he had to “labour with my hands for a support.”2 His Uncle Silas Dinsmoor had written to him from Boone County, Kentucky about property nearby that appealed to his desire for a less stressful life. The wealth and status he had gained from his sugar cane plantation was apparently more trouble than he was willing to deal with and he found something distasteful about slavery in the Deep South that he did not expect to encounter in Kentucky.

Meanwhile, on May13, 1829 James had married Martha Keturah Macomb in Burlington, New Jersey. Because her father had little money to give her in the way of a dowry, it is likely that James married her more for her status and personality. Her siblings had married into several elite northern families, including the DePeyster’s and Livingston’s of New York, and her brother, Alexander, was then serving as the Commanding General of the United States Army. This marriage enhanced James’ own standing and surely brought him some measure of domestic harmony. The couple had three daughters, Isabella, Julia and Susan, before they moved to their farm in Kentucky and James developed a very close relationship with his “dear pets.”

By 1850, Dinsmore had acquired 800 acres in Boone County, Kentucky, and another 200 in nearby Carroll County. Near where Burlington Pike now cuts through his land, he had his brother, John oversee the construction of his large farmhouse that displayed a Greek Revival front to neighbors and visitors, while the backside, with its gallery and smaller service rooms, was more reminiscent of a French Creole residence in the lower Mississippi region. Several years before the Civil War, he and a neighbor bought the Gaines’ Farm in Saline County, Missouri, where they raised hemp. On his Boone County property, James had a vineyard and orchard, and he raised corn, wheat, osier willows for baskets, and sheep and goats for wool. Once again, his role was that of a manager. Although he enjoyed working in his vineyard, he had ten to fifteen enslaved African Americans from Louisiana who labored alongside several white tenants, leaving James free to contemplate life. One might imagine that this is exactly how James dreamed his life would be. The tasks assigned to the enslaved African Americans were not so hated as working in a Louisiana sugar mill but he continued to compensate them for certain jobs, perhaps because the Ohio River and potential freedom were so close.

The wide variety of books in the Dinsmore library attests to James’ faith in progress – agricultural and spiritual. He was constantly looking for new methods of improving the fertility of his land and for different crops for which he anticipated a market existed. Coming from the Deep South, he argued for the raising of hemp in Kentucky which, aside from its use by the navy, was made into cotton bagging. James also experimented with madder, a plant used to make dyes, and silk. The books he read on farming range from viticulture to sheep to honey bees to chemistry and fertilization. But farming was not his only interest—when James went to Cincinnati, which he did often, he attended séances and took his daughters to have their skulls read by a phrenologist. With an unlimited faith in human progress, he investigated most new movements of the nineteenth century, believing that science would eventually lead to human perfection.

As James grew older, his family began to thin out. His youngest daughter’s death in 1851 likely encouraged James’ faith in séances, although he already had a firm belief that he would meet all his loved ones after death. In 1859, his eldest daughter, Isabella, married her first cousin, Charles Flandrau, and moved with him to Minnesota. Seven days later, Martha Macomb Dinsmore died, and only Julia was left to comfort her father. Homesick in Minnesota, Isabella returned home to give birth to her daughter, Martha, in 1861 and returned several times during the Civil War, allowing James to develop a close relationship with his granddaughter, whom everyone called Patty. When Isabella died in 1867, Patty and her sister, Sally, came to live with James and Julia in Kentucky and grew up listening to their grandfather’s stories of his past.

During the Civil War, James supported the Union effort although he was too elderly to fight. He subscribed to the Republican paper in Cincinnati and purchased books about the war before it was even over. However, when one of the enslaved men, David Taylor was drafted in 1864, he paid for a substitute—was it from a sincere desire to keep David safe or was it from a fear of his becoming free? Following the war, one family of African Americans, the Hawkins, remained on the property as tenants and most of the others moved away to Indiana. In his final will, James indicated that Julia was to take care of the Hawkins family and Sally Taylor, a freedwoman who had been brought from Louisiana as a slave with her several children. While it is unclear what Julia did for Sally, she bought a small house in Rising Sun, Indiana for Jilson Hawkins and his family.

The last years of James’ life were quite painful as his body was weakened by rheumatism. Writing to a New York cousin in 1872, he advised him to take care of himself: “O the misery of being old! ...I would not advise you to drown yourself in the Hudson but keep young. Oil your joints with bear’s oil—goose grease—fish worms or some of the patent medicines which I see advertised.”3 As fall crept toward winter in 1872, he weakened considerably and was unable to fight off disease. Although no one named the disease to which he succumbed, pneumonia seems likely. He died on December 21st in his bed that had been moved to the dining room in front of the fireplace and was buried in the family graveyard on Christmas Eve, next to his wife. For months, Julia refused to enter the dining room and for many years afterwards she grew melancholy as Christmas approached.

1 John B. Dinsmore to James Dinsmore, 6 August 1818.

2 James Dinsmore to Martha Dinsmore, 20 February 1839.

3 James Dinsmore to William B. Dinsmore, 29 July 1872.