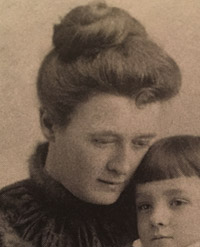

Martha (Patty) Flandrau Selmes

(1861-1923)

In the summer of 1861, as the Civil War was beginning, Isabella Dinsmore Flandrau traveled from her home in Minnesota to Boone County to stay with her father and sister, Julia, while she prepared to give birth to her first child. On August 14th, in a large corner room of the house, Martha Macomb Flandrau was born. Named for her grandmother, her nickname became Patty, and she was doted on by her grandfather, James, and her Aunt Julia before her mother took her back to the cold North. Patty was baptized into the Episcopalian Church, the church of her mother and grandmother. In looks, she inherited her mother’s red hair, which turned to auburn as she grew older, and her father’s dark eyes. She returned to Boone County several times as a child, the last visit being for the birth of her sister, Sally, in late 1866.

In the summer of 1861, as the Civil War was beginning, Isabella Dinsmore Flandrau traveled from her home in Minnesota to Boone County to stay with her father and sister, Julia, while she prepared to give birth to her first child. On August 14th, in a large corner room of the house, Martha Macomb Flandrau was born. Named for her grandmother, her nickname became Patty, and she was doted on by her grandfather, James, and her Aunt Julia before her mother took her back to the cold North. Patty was baptized into the Episcopalian Church, the church of her mother and grandmother. In looks, she inherited her mother’s red hair, which turned to auburn as she grew older, and her father’s dark eyes. She returned to Boone County several times as a child, the last visit being for the birth of her sister, Sally, in late 1866.

Although Isabella was looking pale when she returned to Minnesota in early 1867, no one believed that anything serious might be wrong. By June, she was still not well and wrote to ask Julia to come up and help her with the children. Isabella felt that she was going to die and on June 30th she did. An arrangement had been made that Julia, as the maternal aunt, would take Patty and Sally home with her to Kentucky. There was probably an expectation that in 1871, when Charles Flandrau was remarried to Rebecca Blair Riddle, a widow with a son, John, he would reunite his family. So, in the fall of 1872, it was decided that Patty would attend school in St. Paul in an attempt to bring most of the family under one roof. To distinguish Rebecca from Julia, Patty called her stepmother “Mother” and Julia remained “mommy” or “owny mommy.”

Life in St. Paul started out very well for Patty – she enjoyed her school and was able to go to plays and musicals. But in December when she found out that her beloved grandpa was ill, she became homesick and begged Julia to take her back to Kentucky. After James Dinsmore’s death, Patty was overcome with grief and wrote to Julia:

I can not bear it all alone I am nearly frantic to get to you and Sally.... I will tell you that the only way I stand it is to think that [grandpa] has gone to Mama and Grandma and aunt susy and that they love him as much as we do. It wont (sic) be very long before we are all together and when I think of us all being so happy and good I cant be bad if I try..... My hand shakes so that I can hardly write.1

The experiment of living with the Flandrau family in Minnesota was terminated in the spring of 1873 when Patty returned to Boone County.

From that time on, Charles allowed Julia to make decisions concerning Patty’s education because he realized that she knew his child better than he did. After spending a school year in Akron and living with cousin Sue Goodrich Tew, in September 1874, Julia decided to send Patty to a school in Cincinnati run by Miss Clara Nourse. Patty stayed at the school until she was about to turn nineteen years old and seemed to enjoy herself although Julia noticed several problems that plagued her niece. The worst was Patty’s inability to manage money – she always wanted expensive dresses and went through her father’s money far too quickly. Both Charles and Julia lectured her on this subject. Another problem that Julia noticed was that Patty tended to put on airs when around people she considered beneath her and sometimes ignored them altogether. Her father may have encouraged this by telling her, “Cincinnatians are not the most blue- blooded examples a young person can have. They are not to blame, they have had no ancestors. You have, you come from excellent stock on both sides of the house....”2 Julia tried to make her niece more sensitive to the feelings of others.

Her father also bombarded Patty with advice about her future role as a woman. In his view, innocent flirtations were fine but if she were ever to let down her “affable reserve” then she would be “brought down to the level of the millions of simpletons and littering idiots that go to make up woman kind in general.”3 As to marriage, he made Patty promise to wait until she was twenty-one before she confronted “the question of the happiness or misery of your life.”4 Just one week after her twenty-first birthday, following two active years of socializing in St. Paul, Patty wrote to Julia announcing her engagement to Tilden R. Selmes. Julia, a romantic, was happy for Patty, writing that “young-ladyhood is the most fleeting time in life, and I really think those must be happiest who can marry from pure love in youth.” The couple was married in the parlor at Boone County on June 7, 1883; Patty chose white roses from the front yard for her bouquet. Following the wedding, Tilden and Patty moved to his ranch near Mandan in the Dakota Territory (now North Dakota). While Tilden took up a law career in the town to try to make ends meet, Patty stayed on the ranch with several servants, trying to raise horses. Julia Farley Loving, whom Patty had met in St. Paul, worked for the Selmes family for decades. Out on the desolate plains of the Dakotas, the two women became dependent on each other and learned to get along quite well together.

In 1885, Patty found that she was pregnant. As soon as she was sure of her condition she wrote to her “owny mommy” to ask her if she could return to Boone County to have her child. Of course Julia answered in the affirmative. Patty arrived at Boone (as she called the house) in December and on the 22nd of March she gave birth to a girl in the same room she had been born in. She gave Julia the privilege of naming the child, and Julia chose to give the infant the name of her grandmother, Isabella Dinsmore Selmes. Although Patty took Isabella back to the ranch in the summer, within a year the family had relocated to St. Paul, where Tilden hoped to turn his abysmal financial situation around. In addition to his monetary problems, he was also suffering physically from carbuncles and ulcers. There were happier times when Tilden and Patty could take long trips with friends, such as Theodore Roosevelt, whom they had met when in the Dakotas. They went to the Bad Lands, the Black Hills, and Yellowstone, hunting and sight-seeing. Roosevelt described Patty as “singularly attractive...very well read...a delicious sense of humor, and is extremely fond of poetry.”5 By early 1895, Tilden’s pain was very acute, prompting Patty to take him to see a doctor at Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati and then to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he was diagnosed with liver cancer. Knowing he had only a few months to live, he chose to return to Boone where he died on August 1st, 1895 with his family around him.

After Tilden’s death, Patty stayed behind with her “owny mommy,” while Julia Farley Loving returned with Isabella to St. Paul, where they were to live with Flandrau family. At Boone, Patty struggled to bring her feelings under control, writing her step- mother, “I must get my mask made and fitted on before I face the world.”6 Since Tilden had not been able to leave her much of an income, she decided to start a ham business on Julia’s farm with an old school friend. This kept her away from Isabella for several months out of the year, a matter that Patty and Rebecca Flandrau argued about several times, but Patty enjoyed being able to make her own money and her hams were feasted on as far away as the White House.

Even though Patty resorted to drinking to hide her depression following the death of her husband, it did not appear to damage her relationship with her daughter, who constantly sought her advice and never appeared to resent their time apart. Isabella later wrote that, “Mother’s & mine was the great & perfect of human relationships. We adored & worshipped each other & our love kept each other alive as the sun brings life to the earth.”7 Thinking primarily of her child, in 1901 Patty accepted an offer from her sister, Sally and Frank Cutcheon to live with them in New York City so she could send Isabella to school there. Charles Flandrau agreed to pay tuition and even gave Patty $1500 for a trip to Europe in 1903. He died while they were still abroad. Because he had already given Patty $10,000 since Tilden’s death, he left her no legacy in his will. But the fact that he left nothing for Sally, strained the relationships within the Flandrau family.

Upon returning to the United States, Patty prepared herself for Isabella’s upcoming debutante season, where the latter was proclaimed a great success. Rather than choosing one of the young, eligible bachelors, though, she became engaged to Robert Munro Ferguson (Bob), a thirty-seven year old former Rough Rider and friend of President Theodore Roosevelt. Patty was very affected by the match, though the reason is unclear. Bob had visited the Selmes family when they were living in St. Paul and there is even a letter to him from Patty, so it is possible she considered him to be more of her acquaintance than her daughter’s. Another cause of friction was the wedding itself, which was a very small affair that took place at the Cutcheon house in Long Island. In Patty’s letter to Julia the day of the wedding, Patty sounds as though what most upset her was that her role as mother-of-the-bride was significantly diminished. “I feel I might just as well have stayed in Boone as far as having any part in any of it but shall make it the object of the next few days to try and not let any one see how I feel in any way and don’t think it will be hard as I don’t think any one cares.”8 She was only allowed to invite two of her friends and Isabella had only one friend present while Ferguson had about ten acquaintances there, including President Roosevelt with some of his children and Dave Goodrich, the son of B. F. Goodrich, who was Bob’s best man. No doubt feeling alone and adrift now that her duties as a mother appeared to be at an end, Patty began to travel more, making sure to spend several months each year at Boone with Julia.

In 1906, Isabella gave birth to a daughter, whom she named after her mother, Martha. Patty enjoyed her role as grandmother and two years later, a grandson was added to the family, named Robert. When Isabella and her family moved to New Mexico in 1910, Patty went out and stayed in tents with them, giving lessons to her grandchildren since there was no school nearby. She also took several trips to Europe and was even stranded in Germany when World War One began in 1914, though she made it safely back to the states. Isabella built a small house for her mother at her Burro Mountain Homestead near Tyrone, New Mexico, and another in Santa Barbara. In the last years of her life, Patty suffered from pleurisy, nerves, and digestive problems and often complained that no one took her troubles seriously. She died in the early morning hours of July 18, 1923, far from Boone, in the mountains of New Mexico. She requested that her body be cremated and her ashes buried with Tilden in the family graveyard. Patty’s death hit her “owny mommy” very hard, but Theodore Roosevelt’s sister, Corinne R. Robinson wrote to comfort her, “Oh! How she loved Boone, & the room she had as a child, & all of its memories. No one could love as Patty loved, or do for those she loved as Patty did. I feel starved when I think of trying to do without her love, which she gave me so generously & freely.”9

1 Patty Flandrau to Julia Dinsmore, 29 December 1872.

2 Charles Flandrau to Patty Flandrau, 1 February 1878.

3 Charles Flandrau to Patty Flandrau, 8 March 1879.

4 Ibid.

5 Quoted in Joseph P. Lash, Love, Eleanor: Eleanor Roosevelt and Her Friends (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1982), 52.

6 Patty F. Selmes to Rebecca B. Flandrau, 6 August 1895.

7 Isabella S. Ferguson to Mary Selmes, 14 August 1923.

8 Martha F. Selmes to Julia Dinsmore, 13 July 1905.

9 Corinne R. Robinson to Julia Dinsmore, 19 July 1923.